The (not-so) Major Confusion of Row-major and Column-major Matrices

02 December, 2024

- Math Notation and Pre/Post-Multiply

- Examples

- What about matrix multiplication order?

- One More Example

- Useful Links/Resources

I’ve always had trouble remembering which order I should apply matrix multiplications in code, or which side the vector should go on for a matrix transform. Obviously the order is important; you’ll get very strange results if you get it wrong, but the devious thing about matrix math is that you’ll often also get bizarre results if your math is just wrong in some other way. It definitely pays to save yourself the future headache and get this right. It’s also not that complicated when it comes down to it.

“You didn’t know all this already?” No, I didn’t know all of this already.

Math Notation and Pre/Post-Multiply

There are two main conventions for matrix-vector multiply, and those are pre-multiply and post-multiply.

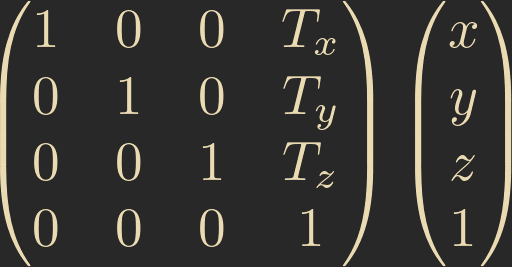

Post-multiply is the most dominant by far, especially in mathematical texts and really everything other than computer graphics. It represents the vector as a single column matrix on the right side. Like this:

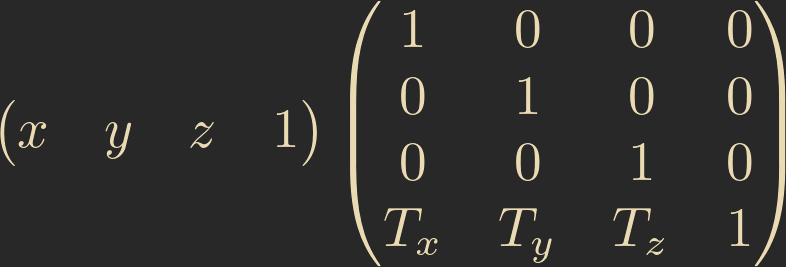

There is also pre-multiply, which represents the vector as a single row matrix on the left side. That looks like this:

You can flip between the two matrix representations by transposing the matrix (reflecting it along its diagonal).

There is no good reasoning for these competing styles. People are just opinionated and one feels better than the other to some. The pre-multiply convention appeared in the DirectX SDK at some point, so that’s probably why it’s more common in graphics. Not necessarily more common than post-multiply, just more common than in other fields.

I’m not too interested in discussing what the actual operations are that happen when you pre-multiply or post-multiply. The core question is: how do we know which is correct in a given situation? The answer to this depends primarily on your math library, and the convention the author preferred. This was pretty surprising to me, but is obvious in hindsight.

In most game math libraries, a Matrix4 type is stored as 4 Vector4 types:

struct Mat4 {

Vector4 m_elem0;

Vector4 m_elem1;

Vector4 m_elem2;

Vector4 m_elem3;

};

Now, referring back to matrix notations above; does each vector represent a single row, or a single column of the matrix? This is the fundamental difference between libraries. Depending on which is used, it is implied that the translation components live in either the last column (if vectors represent columns) or the last row (if vectors represent rows) of the matrix above, and this is what defines whether you should pre-multiply or post-multiply.

The technical terminology you’ll hear is row vectors if your vectors are rows and column vectors if your vectors are columns.

This detail is obscured by the fact that you’ll often hear it referred to as the library using either column-major or row-major matrices, but row-major and column-major are also computer science terms used to define how 2D arrays are stored in memory, which might lead to you scratching your head on this wikipedia page. This is a decision made by the programming language and totally irrelevant to what we’re talking about here. Our matrices are not even using 2D arrays! When using either convention, the byte storage ends up being identical due to the translation components being flipped, so the storage method really doesn’t tell us anything meaningful here.

Some people might try to tell you that when you hear “row-major” or “column-major” you should think purely of storage and nothing else, but the reality is that much of the world uses this terminology to discriminate between row vectors and column vectors.

Examples

Let’s look at some math libraries and see if we can figure out which convention we should be using.

VectorMath

The aptly named VectorMath is a vector/matrix math library that was open sourced by Sony around 2007. Its matrix class is defined in the following way:

// vectormath.hpp

VECTORMATH_ALIGNED_TYPE_PRE class Matrix4

{

Vector4 mCol0;

Vector4 mCol1;

Vector4 mCol2;

Vector4 mCol3;

...

}

We can easily guess that each element is intended to represent a column in a matrix. But where are the translation components stored?

// matrix.hpp

inline const Vector3 Matrix4::getTranslation() const

{

return mCol3.getXYZ();

}

Cool, this totally aligns with our column vector math notation above. So we’d expect to use post-multiplication here. Let’s take a look at the operator overloads:

// matrix.hpp

inline const Vector4 Matrix4::operator * (const Vector4 & vec) const

{

return Vector4(((((mCol0.getX() * vec.getX()) + (mCol1.getX() * vec.getY())) + (mCol2.getX() * vec.getZ())) + (mCol3.getX() * vec.getW())),

((((mCol0.getY() * vec.getX()) + (mCol1.getY() * vec.getY())) + (mCol2.getY() * vec.getZ())) + (mCol3.getY() * vec.getW())),

((((mCol0.getZ() * vec.getX()) + (mCol1.getZ() * vec.getY())) + (mCol2.getZ() * vec.getZ())) + (mCol3.getZ() * vec.getW())),

((((mCol0.getW() * vec.getX()) + (mCol1.getW() * vec.getY())) + (mCol2.getW() * vec.getZ())) + (mCol3.getW() * vec.getW())));

}

// vector.hpp

// <none>

So there’s not even an operator overload for pre-multiplication. The library is clearly telling us that it uses column vectors and post-multiplication, which matches with the standard mathematical notation. If we wanted to be super sure we could also have a proper look at that multiplication operator and make sure that it’s doing what we expect.

This is an example of an opinionated library that really wants there to be a single correct representation for a transformation matrix, and that’s with the translation components in the final column.

zmath

Now let’s take a look at zmath, which is also a SIMD math library for game developers, for the Zig programming language.

Most people aren’t familiar with Zig, so I’ll try to do a bit more explaining here.

// zmath.h

// Fundamental types

pub const F32x4 = @Vector(4, f32);

...

// "Higher-level" aliases

pub const Vec = F32x4;

pub const Mat = [4]F32x4;

pub const Quat = F32x4;

We can see that zmaths matrix type is also backed by an array of 4 F32x4s, which themselves are a group of 4 floats. In Zig, types created with @Vector() are operated on in parallel, using SIMD instructions if possible: https://ziglang.org/documentation/master/#toc-Vectors.

Unlike the Sony library, the fields aren’t named, so we don’t get any clues there. They could represent either rows or columns.

Let’s look at how a translation matrix is created:

pub fn translation(x: f32, y: f32, z: f32) Mat {

return .{

f32x4(1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0),

f32x4(0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0),

f32x4(0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0),

f32x4(x, y, z, 1.0),

};

}

Looks like zmath stores the translation in the final element, just like Sony’s library. But should we use pre or post-multiplication? Let’s have a look at the matrix multiplication:

pub fn mul(a: anytype, b: anytype) mulRetType(@TypeOf(a), @TypeOf(b)) {

const Ta = @TypeOf(a);

const Tb = @TypeOf(b);

// other types stripped ...

if (Ta == Vec and Tb == Mat) { // vector vs matrix "overload".

return vecMulMat(a, b);

} else if (Ta == Mat and Tb == Vec) { // matrix vs vector "overload".

return matMulVec(a, b);

} else {

@compileError("zmath.mul() not implemented for types: " ++ @typeName(Ta) ++ ", " ++ @typeName(Tb));

}

}

This might be a bit Ziggy and hard to follow. Zig doesn’t have operator overloading, but it does have very good type information and compile time abilities. Multiple independent versions of this function will get compiled, according to the types passed in.

Critically, zmath lets us do either pre-multiply or post-multiply. Unfortunately, now we need to look at which version is correct, given that our translation components are in the last element:

fn vecMulMat(v: Vec, m: Mat) Vec {

var vx = @shuffle(f32, v, undefined, [4]i32{ 0, 0, 0, 0 });

var vy = @shuffle(f32, v, undefined, [4]i32{ 1, 1, 1, 1 });

var vz = @shuffle(f32, v, undefined, [4]i32{ 2, 2, 2, 2 });

var vw = @shuffle(f32, v, undefined, [4]i32{ 3, 3, 3, 3 });

return vx * m[0] + vy * m[1] + vz * m[2] + vw * m[3];

}

fn matMulVec(m: Mat, v: Vec) Vec {

return .{ dot4(m[0], v)[0], dot4(m[1], v)[0], dot4(m[2], v)[0], dot4(m[3], v)[0] };

}

If you’re like me, you won’t intuitively know which of these is right, and you’ll just need to do it the hard way by manually verifying, or writing some test code:

const translation = zm.translation(0.0, 99.0, 0.0);

const point = zm.f32x4(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

const post_mult = zm.mul(translation, point);

const pre_mult = zm.mul(point, translation);

std.debug.print("post_mult: {any}\npre_mult: {any}\n", .{ post_mult, pre_mult });

$ ./out

post_mult: { 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0 }

pre_mult: { 0.0, 99.0, 0.0, 1.0 }

Ok, so post-multiplication did nothing and pre-multiplication produced the correct result, so zmath must use row vectors. What if we manually make a matrix and store translation at the end of each element instead?

// Translation stored on the "right" instead of the "bottom".

const translation = zm.Mat{

zm.f32x4(1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0),

zm.f32x4(0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 99.0),

zm.f32x4(0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0),

zm.f32x4(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0),

};

const point = zm.f32x4(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

const post_mult = zm.mul(translation, point);

const pre_mult = zm.mul(point, translation);

$ ./out

post_mult: { 0.0, 99.0, 0.0, 1.0 }

pre_mult: { 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0 }

Now post-multiplication is correct. So I guess this is just zmath supporting both row and column vectors and letting the user decide, even though post-multiplication won’t work with a matrix created via zm.translation().

I’m not a fan of this kind of implementation, especially given that this library is advertised as a library for game developers.

Shader languages also commonly let you multiply things in any order, which is also a source of confusion. If you upload your zmath matrices to the GPU and run your WGSL shader on them, you’ll have to flip to using post-multiplication instead, unless you transpose your matrices before upload. This is because WGSL treats matrices as column vectors:

A matrix is a grouped sequence of 2, 3, or 4 floating point vectors. The key use case for a matrix is to embody a linear transformation. In this interpretation, the vectors of a matrix are treated as column vectors.

The fact that you could have a shader that uses pre-multiply for some matrices and post-multiply for others is wild to me, but ultimately make sense.

So there you have it. Two libraries using identical memory representations but different conventions around multiplying matrices. All that matters is what the math library actually does. In hindsight it’s obvious.

What about matrix multiplication order?

One good thing is that once you’ve figured out pre or post-multiply, the rules are the same for matrices, unless you’re using the math library of a madman…

If using pre-multiplication (row vectors), then matrices should be combined left-to-right:

// A matrix that takes you from local to world space, then from world space to clip space.

Matrix object_to_clip = object_to_world * world_to_clip;

Vector4 result = local_pos * object_to_clip;

If using post-multiplication (column vectors), then matrices should be combined right-to-left:

// A matrix that takes you from local to world space, then from world space to clip space.

Matrix object_to_clip = world_to_clip * object_to_world;

Vector4 result = object_to_clip * local_pos;

One More Example

To make things abundantly clear, here’s how a typical vertex shader in GLSL (which uses column vectors – post-multiplication) would calculate gl_Position, given raw matrices from VectorMath that have not been transposed:

layout(location = 0) in vec3 inPosition;

uniform mat4 objectMatrix;

uniform mat4 projectionMatrix;

void main()

{

gl_Position = projectionMatrix * objectMatrix * vec4(inPosition, 1.0);

}

And here’s what it would look like if you uploaded the raw matrices from zmath without transposition:

layout(location = 0) in vec3 inPosition;

uniform mat4 objectMatrix;

uniform mat4 projectionMatrix;

void main()

{

gl_Position = projectionMatrix * objectMatrix * vec4(inPosition, 1.0);

}

They’re the same! Of course they are – the underlying memory representation is the same in both libraries. The difference is that we’re switching to GLSL’s math library, which uses column vectors, and interprets our matrices as columns of vectors.

If this all makes sense to you then you probably understand the concept enough to never be bothered by it again.

Useful Links/Resources

- A catalogue of the differences between shading languages, including information about their matrix representations: https://gist.github.com/teoxoy/936891c16c2a3d1c3c5e7204ac6cd76c#21-storage-address-space

- Another good explanation on the Khronos forums: https://community.khronos.org/t/row-major-vs-column-major-in-4-1/64122

- Matrix multiply confusion, and an OpenGL author dispelling it: https://steve.hollasch.net/cgindex/math/matrix/column-vec.html

- A more detailed explainer that goes into the math, as well as coordinate spaces: https://seanmiddleditch.github.io/matrices-handedness-pre-and-post-multiplication-row-vs-column-major-and-notations/

- Another explainer: https://austinmorlan.com/posts/opengl_matrices/

- Pretty useful overal resource on OpenGL transformations: https://www.opengl.org/archives/resources/faq/technical/transformations.htm